China Letter 6 - Nanjing, Zenith, River eel - 10/12/25 - Jin ri zi du, Qingdao

On my flight to Nanjing, a stewardess spoke to me in the silence of the cabin. I didn’t understand what she meant. I assumed an issue. My dinner tray was down to hold my notebook, but my neighbor’s tray was down too. She tried to borrow my pen. I didn’t want her marking up the page as I was working on a notebook poem, then she said,

“I need to practice my English.”

“Oh.”

“I will go to the bathroom.”

“Okay.”

She returned momentarily and asked what I was writing.

“A poem,” I explained.

“Can I read?”

“No. It’s not finished.”

Later on, another stewardess came over with a note from the first. On a paper bag, written with red makeup, it said, “Good luck…One road” in Chinese and English. On the back of the bag, she had written, “hope you can write perfect poem.”

For the metro in Nanjing, you use a plastic coin instead of a card to pass through the turnstiles. You don’t keep the coin, nor do you keep the cards in Qingdao, so they are forever rotating tokens that never make it out of the subway.

Upon arrival, I found my hotel. I had selected a bed in a male dormitory in the Zunjing Academy Hotel because it looked the most adventurous and had good reviews. It is just next to the Confucius Temple. Actors perform skits on a stage in the courtyard, so there’s animated shouting at night. The breakfast is good. It’s clean. Zunjing Academy Hotel is a good stay. The name means “Respecting Classics.” The Qinhuai River District is lively with ducks in the windows, souvenir-shops, and museums. People wear costumes for the Mid-Autumn festival. The first day, I learned about the 1,300 year old history of the Imperial Examination system in a museum dedicated to that. When you walk in, there is a 130 meter long ramp and tens of thousands of bamboo slips since examination candidates “read tens of thousands of books and walk tens of thousands of miles.” The museum is four floors underground. Chinese consider the exam one of their greatest inventions and a continuing influence on standardized testing though this civil exam was abolished in 1905. It is described as a “spiritual contribution” to the world and a representation of “soft power.” After that, I saw a transnational exhibition of still lifes on the eighth floor of a mall, including magnificent paintings from Chinese, European, Indian artists and more. There was a plump vase of sunflowers by Botero.

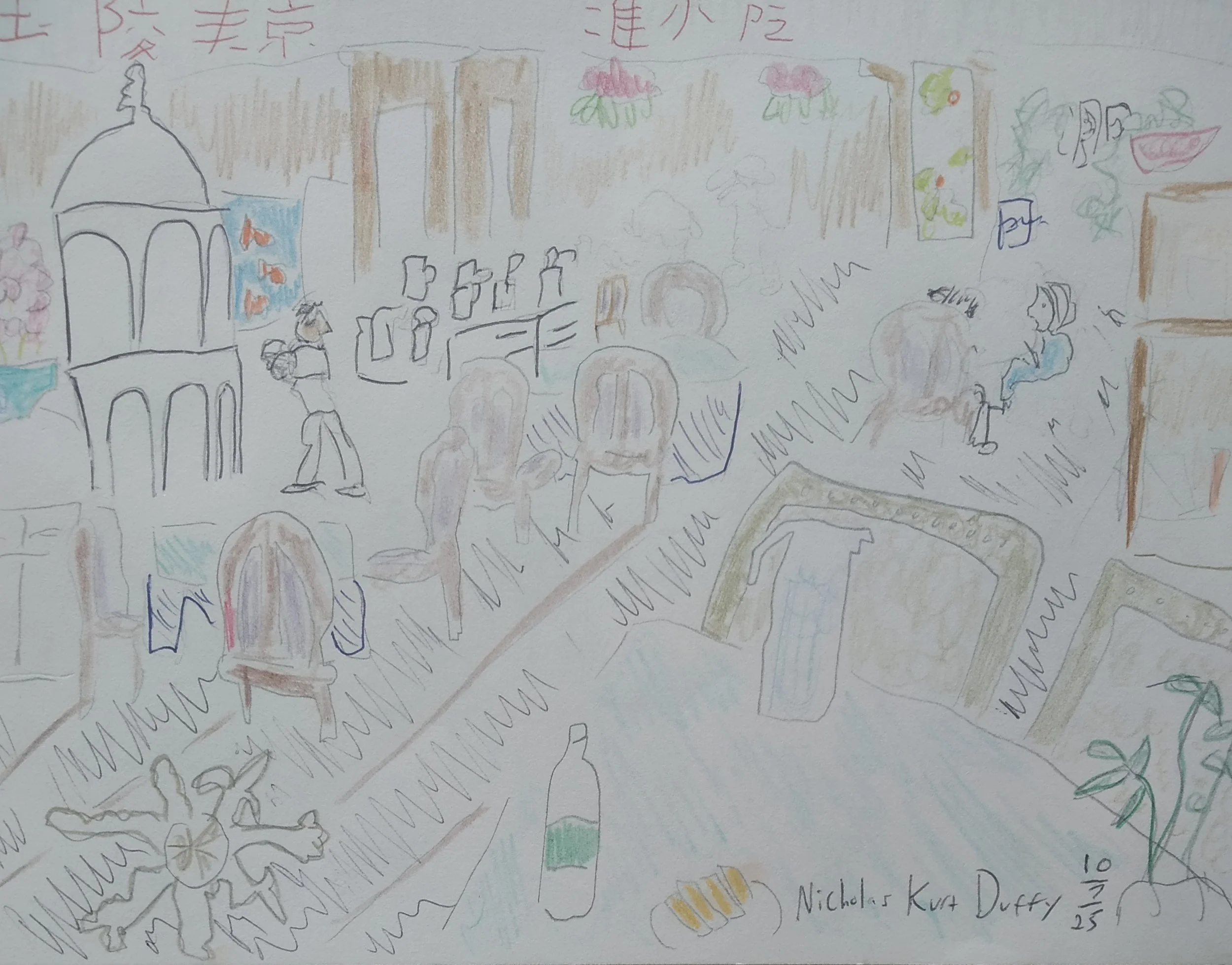

I had a good dinner that night in a tea house by the hotel:

The second day, I walked near enough to Nanjing University and Southeast University, then visited the Jiming Temple. It is built uphill, so one raises their eyes to the heavens and sees slanting roofs until they reach the pagoda up several flights of stone stairs. Yellows and reds and black roof tiles. There is the sweet smell of incense; on the day I visited in particular, it was the last day of the national holiday, so people were burning incense and bowing to pray for a good return to work and school. There are many halls. By the pagoda, there’s a hall with a buddha on a lotus. The statue is in front of an altar holding waters, fruits, and amethyst.

The Ming Wall is next to the Jiming Temple so I went there next, sat for a bit to do a drawing, then walked on the well-preserved ancient wall, glancing now and then to the Xuanwu Lake until I got to a gate. I carried on right to the Purple Mountain and up to the zenith at 449 meters. I passed enumerable people on that beautiful day.

The dorm had initially been shared by myself and a German who left, and that night two boisterous Russians showed up.

The third day, I confirmed that my train ticket was bought at the Nanking South Railway Station, and then I went to The Memorial Hall of Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders. I read The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang a couple weeks ago after hearing it referenced by Jordan Peterson years back. As Peterson alluded to it in context, so does the author depict this event; it is evidence of people losing their humanity all together. The memorial estimates more than 300,000 murders from December 1937 to January 1938. The massacre was denied for a long time by Japan, and the event is making its way into popular consciousness through the work of scholars, journalists, videographers, and courts.

There was a long line for the memorial. People were purchasing white chrysanthemums to leave on the ground. When you enter the space, there are statues of people in despair, like a giant, melting woman who is so tall you feel vertigo trying to look up as you’re in a narrow space between the memorial and the gate. The statues are accompanied by verses that describe the evil. The ground is very flat, so the long open space laid with stone, tall jutting statues, and the sharp black building are jarring. When you walk in, the first chamber is black and this black extends through various exhibition halls. There are photos of the deceased and also of survivors. The memorial includes original documents, model sets of destruction, and an excavation area where you see skeletons, this memorial having been constructed on one of many mass graves. There are video testaments from survivors. An area representing Xin Shuqin reads,

“I was born in May 1929. On December 13, 1937, a team of Japanese soldiers broke into my house at No. 5 Xinlukou, east to Zhonghua Gate in Southern Nanjing. They slaughtered seven members of my family for no reason at all: my grandfather Nie Zuocheng (aged over 70), my grandmother Nie Zhou (over 70), my father Xia Ting’en (over 40), my mother Xia Nie (over 30), my eldest sister Xia Shufang (16), my second eldest sister Xia Shulan (14), and my youngest sister Xia Shufen (barely older than 12 months). My mother and my two elder sisters were gang-raped by the Japanese soldiers. Then 8-years-old, I was stabbed three times and fainted. I would eventually wake up and survive the killing with my 4-year-old younger sister.”

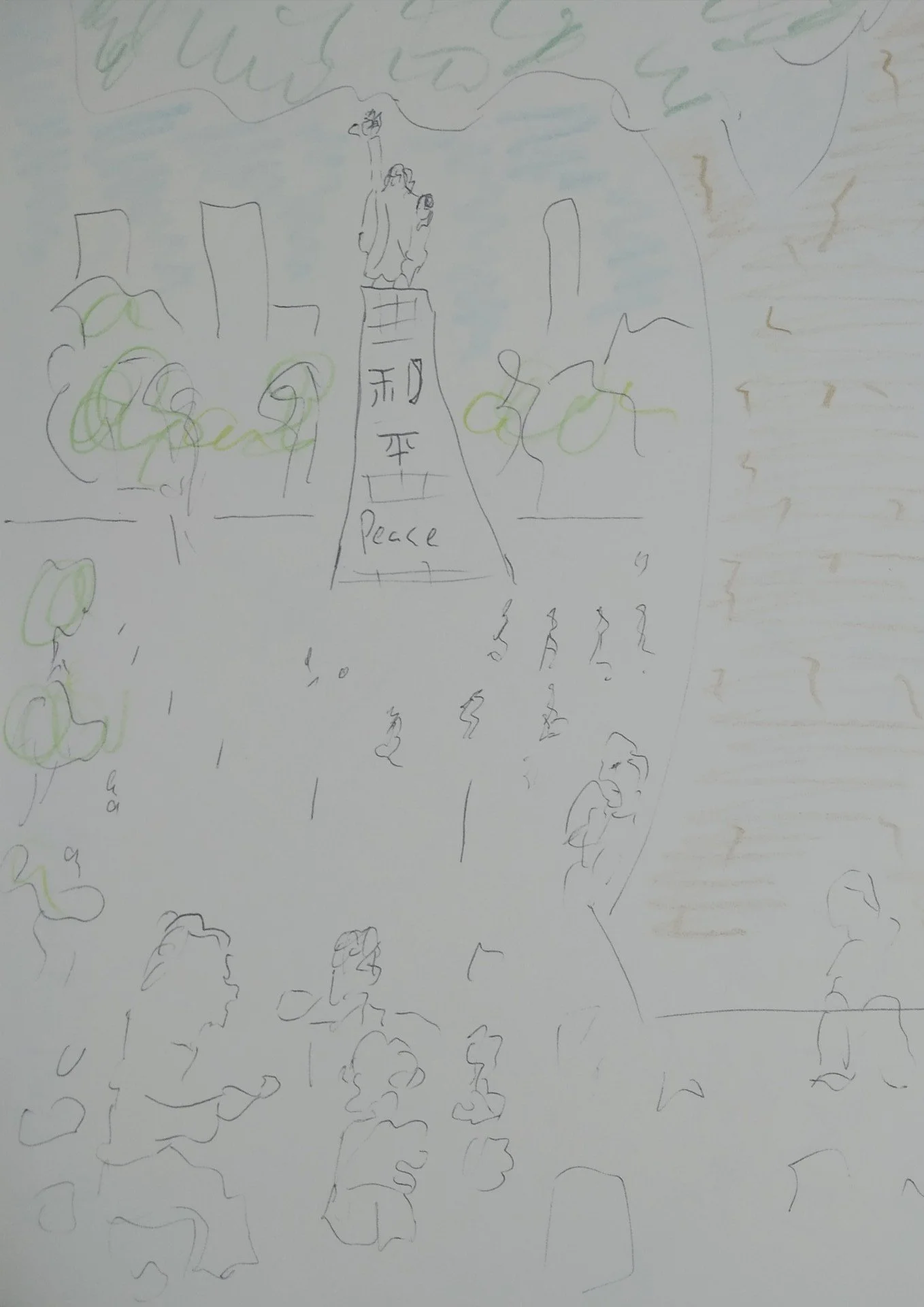

I found myself crying at times when I was out of the crowd. The people there could have had relatives involved and know it is a dark spot in their nation’s history. Yet, the sadness is not depressing, is it? Rather, it’s inspirational. Not everyone is concerned with history or international things, and it makes sense at times since we all must do our best for our immediate families, but I believe there is a lot of good we can do when we watch our own ignorance in our households, for an event like the Nanjing Massacre is more evidence that, all over the earth, people have simultaneously experienced terror and gotten new surveillance and communication technologies that show we are all human, now. We must keep moving what is terrible, what is reasonable, and what is possible about human nature forward and cannot accept that we do not change human nature by how we think individually and in private. That is the good work we can do. Just knowing we don’t know, and identifying what is not peace and not participating in that conflict, at all, which ironically takes the cognitive discipline of a great soldier or monk. Considering such an event as the Nanjing Massacre and letting it affect your understanding is clear evidence of the good of a book versus what we might find ourselves saying or using for language after seeing sensational media about a foreign country and its people. I would like to be someone who assures you the better choices you make alone do have an impact and contribute to our general improvement. Actively appreciate. What we need is so immediate it is not culminated in protests or media buzz, rather it is seamlessly happening whenever we pacify.

It was possible for me to lay eyes on the Yangtze River, so I walked willy nilly west of the tearjerking memorial pretty far through nothing scenic, found my view obstructed by a hotel, went in to see if there was some way to see, was recommended a direction, and kept walking until I found a certain park. I sat against a tree and saw a small, brown section of the third-longest river on earth. That afternoon, I chose a dozen new titles from Nanjing’s Phoenix International Book Mall and Foreign Language Bookstore as planned, for English books are scarce in Qingdao. I found some great stuff. The Foreign Language Bookstore has several shelves and tables holding imported books. Instead of a bag, the books were wrapped in a tarp-like paper and tied. I carried my package onto the metro by the ribbon like a literati.

That night, I had dinner with Chuan, who was my flatmate in Edinburgh. He is now an architect in Nanjing and a father of two. I tried chicken feet, which aren’t bad if prepared as I had them because they are tender rather than like you’d expect when chewing talons. And I also tried river eel. Chuan and I walked in another zone of the Qinhuai River District. He showed me restored buildings, another section of the Ming Wall, and the Grand Baoen “Porcelain” Pagoda restored in glass, which is lit up green at night. Apparently things are seldom constructed in porcelain anymore, so after last week’s letter, I’m unsure if the holes one squats to use are really porcelain. We took a taxi to where Chuan lives so that I could see the river from another point of view. He lives in an area that had hosted the youth olympics in 2014, so there are many buildings built with creative liberty from generous funding; we crossed the Nanjing Eyes, a pedestrian bridge.

The next day I rode the train home over hundreds of miles of Chinese countryside.

Cheerio,

Nick

To reply, email nicholasthepoodlebooks@outlook.com